Be kind, Bee mind

(sorry)

I’ve been on a break from work for the last few months, and one of the things I’ve been doing is learning more about the brain: by taking Computational Models of Cognition as part of Berkeley University’s Summer Sessions, doing the (excellent) Brain Inspired Neuro-AI course, and of course listening and reading around the topic. I’ll write more about this another time, maybe.

I was charmed by this interview on the Brain Inspired podcast with Mandyam Srinivasan. His career has been spent researching cognition in bees, and his lab has uncovered a ton of interesting properties, in particular how bees use optical flow for navigation, odometry and more. They’ve also applied these principles to drone flight - you can see some examples of how here.

Some of the mechanisms they discovered are surprisingly simple; for instance, they noticed that when bees entered the lab through a gap (like a doorway), they tended to fly through the center of the gap. So they set up experiments where bees flew down striped tunnels, while they moved the stripes on one side, and established that the bess were tracking the speed of motion of their field of view through each eye, and trying to keep this constant. Bees use a similar trick when landing: keeping their speed, measured visually, at a constant rate throughout. As they get nearer to the landing surface, they naturally slow down. Their odometry also turns out to be visual.

The algorithm for centering flight through a space is really simple:

- Convert what you see to a binary black-and-white image.

- Spatially low-pass filter (i.e.blur) it, turning the abrupt edges in the image into ramps of constant slope.

- Derive speed by measuring the rate of change at these ramps. If you just look at the edge of your image, you’ll see it pulses over time: the amplitude of these pulses is proportional to the rate of change of the image and thus its speed.

- Ensure the speed is positive regardless of direction of movement.

Srinivasan did this using two cameras, I think (and his robots have two cameras pointing slightly obliquely). I tried using a single camera and looking at the edges.

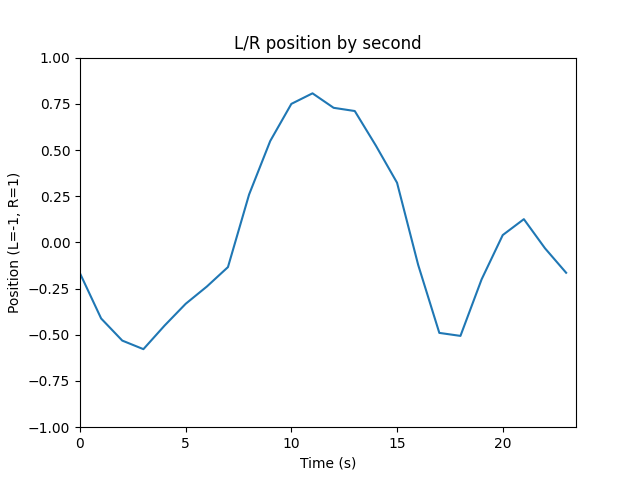

It seems to work well on some test footage. Here’s a video I shot on a pathway in Sonoma, and here’s the resulting analysis which shows the shifts I was making between left and right during that walk, quite clearly:

Things I’m wondering about now:

- Making it work for robots: specifically, can I apply this same mechanism to make a Donkey car follow a track? (I’ve tried briefly, no luck so far)

- Do humans use these kinds of methods, when they’re operating habitually and not consciously attending to their environment? Is this one of a bag of tricks that makes up our cognition?

- What’s actually happening in the bee brain? Having just spent a bit of time learning (superficially) about the structure of the human brain, I’m wondering how bees compare. Bees have just a million neurons versus our 86 billion. It should be easier to analyze something 1/86000 of the size of the human brain, no? (fx: c elegans giggling)

Srinivasan’s work is fascinating by the way: I loved how his lab has managed to do years of worthwhile animal experiments with little or no harm to the animals (because bees are tempted in from outside naturally, in exchange for sugar water, and are free to go).

They’ve observed surprisingly intelligent bee behavior: for instance, if a bee is doing a waggle-dance near a hive to indicate food at a certain location, and another bee has been to that location and experienced harm, the latter will attempt to frustrate the former’s waggle-dance by head-butting it. That seem very prosocial for an animal one might assume to be a bundle of simple hardwired reactions! After reading Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Metazoa earlier this year, has me rethinking where consciousness and suffering begin in the tree of life.

I’ve put the source code for my version here.