LIFT07: The Luminous Bath: our new volumetric medium, Ben Cerveny

February 08, 2007 | CommentsLIFT07: The Luminous Bath: our new volumetric medium, Ben Cerveny

What does it mean to be in a world of pervasive computing? Since culture started, we've been piling meaning onto objects. Information is "spilling out into space".

What does it mean to be in a world of pervasive computing? Since culture started, we've been piling meaning onto objects. Information is "spilling out into space".

Fluidity of attention: "an enormous viscosity of experience blankets the places where we live and work".

Suspension of beliefs: digitally mediated artefacts are created by ourselves out of our attention and are suspended in it.

Memotaxis: all around us are other shards of attention, of other peoples experiences. These objects gather metadata as they receive attention and form more complex structures based on the relationships caused by this metadata.

Aggregate morphologies: (or mashups)

Accretion: in a fluid medium, there isn't a hard line between an object and the medium in which it sits.

Signalling: we have mobile objects, ambient displays, other objects in the environment through which this data flows.

Schooling: organisation on a collective level isn't available to members of a group, in the same way that the shape of a school of fish isn't visible to members of that school.

Decanting: you distil a package of information out of the network, e.g. taking a dump of wikipedia and place it in a static form onto a laptop.

Crystallizing: creating a useful but temporary structure from information.

Lots of biological metaphors here. Talk of "intelligent information", etc.

I think I can summarise bits of this as:

- We attach meaning to stuff

- We record this meaning digitally

- We categorise this meaning

- We aggregate these categories

- Stuff blends into its environment

- We can get the meaning out of stuff and expose it

- You can't normally see how this works from the inside

I don't think I understood this fully, but maybe I'm just really tired. I got a bit lost at the moment when the information starts to exhibit behaviour under its own steam...

LIFT07: Social = Me First, Stowe Boyd

February 08, 2007 | CommentsLIFT07: Social = Me First, Stowe Boyd

Member of the Web 2.0 and Media 2.0 workgroup. The title of this talk sounds selfish - a few people complained about it.

With the emergence of Web 2.0 social apps, the old idea of "membership of groups" has faded, to be replaced with the idea of "the individual at the centre of their own world". The most successful social apps are the ones which allow people to pursue what they're interested in foremost, and handle their affiliations with other people after that. Me first: my passions, my people, my markets.

If you build apps to let people do what they want, you abdicate authority. People end up becoming the rule making organisation: "the edge dissolves the centre". Eventually people affiliate based on shared interests - they self-organise. My view of "people who like the music I do" doesn't necessarily map to someone else's - even if they're in my group. Groups are based around individuals.

Stowe describes himself as a psychiatrist for social software, often called in when it's not working.

Stowe describes himself as a psychiatrist for social software, often called in when it's not working.

If you can't see anything about the person who's logged in, it's a bad sign: there's no "me". Related to me are other people who share my interest. And beyond that the application can provide a platform to provide a marketplace for trading insights, goods, etc. In lots of cases, the market comes first: e.g. searching for music in a predefined way, then a tab with "your friends" is added as an afterthought. This is why there are hundreds of social software companies dying: they get this backwards.

The buddy list is the centre of the universe: "I am made greater by the sum of my connections, and so are my connections". Most of a network is connections.

The fundamental driver for people online is discovery: they want to discover more about the world. Things (e.g. music) are a side-effect. What they want are places where they can learn about things like music.

Not sure I agree with this: wasn't Napster and all the file-sharing software the ultimate expression of discovery? Didn't that completely eschew any form of communication or community?

LIFT07: Open-ended play in Habbo

February 08, 2007 | Comments Open-ended play in Habbo Hotel, Sampo Karjalainen, Chief Creative Officer, Sulake

Open-ended play in Habbo Hotel, Sampo Karjalainen, Chief Creative Officer, Sulake

Talking about open-ended play in Habbo: thought of as a game, but it's goal-less, it's more of an open environment. Over 7m unique users in all the localised Hotels each month. Media age is 14 - it was designed for 13-16 yr olds. Japanese/Brazil users tend to be older. 51% girls, 49% boys.

There's the environment + a console (for in-world messaging), and in-game games. Traditional multiplayer stuff in teams, competing against other players: diving, snowball fights, etc.

What's making users come back? Users can create their own rooms and start furnishing them. They populate these rooms from a catalogue and there's a trading/collection mechanic in there too, with trading rooms etc. All kinds of activity rooms: running rooms, teleporters, etc. Users can set up quests in their rooms too.

There are adoption rooms, and "stables" where some players look after others. Traders trade items in ebay, there are fan sites ("Habbo Meadow"), and other mechanisms for supporting in-world activities. Habbo users can also make their own web pages very easily.

They love to play like kids do. They're not kids any more, they're teenagers but in an online environment they can play together. It's not cool for kids of that age to say they play, so Habbo can't use that in their marketing, but they still love it.

They love to play like kids do. They're not kids any more, they're teenagers but in an online environment they can play together. It's not cool for kids of that age to say they play, so Habbo can't use that in their marketing, but they still love it.

Thoughts on doing this stuff:

- Avatars, lego, even the words and letters of chat, are all building blocks for playful interaction.

- If you let users move, rotate, colour, transform and stack items in the world, this supports play better than the simple interactions that occur in the browser environment.

- Keep the UI invisible: dialogs get in the way of the flow of play.

- Set up a mood for play. Try to minimise utilitarian for-profit thinking and "celebrate the fun of doing".

- Let players choose their own goals. High scores and rankings make things very one-dimensional.

- When you design for play, people will come up with all sorts of unexpected stuff: but you still need to get some sort of idea of what might happen.

- The bonus multiplier for this stuff is putting it into a shared social setting: this is when it gets interesting. It's difficult to build interesting play environments or toys for a single user, but easier in a social setting.

I wonder.... how does Habbo sustain itself commercially?

Q: How much do kids spend in the hotel?

A: A large chunk of users play for free. 10% pay for it, about 10 euros pcm.

LIFT07: Literacy, Communication and Design, Jan Chipchase

February 08, 2007 | CommentsLIFT07: Literacy, Communication and Design, Jan Chipchase

Works for Nokia Design in Tokyo. The task: "design a phone for illiterate people".

Shows up the UN definition of literacy. The core function of a phone is to transcend space and time: crossing great distances and enabling asynchronous communication, in a personal and convenient manner.

It's better to solve the root causes of a problem than design around it.

Is there a point in our evolution where textual literacy becomes redundant?

799 million illiterate people on the planet, 270m of them in India but illiteracy is everywhere. Lots of folks use devices that don't support their native language.

799 million illiterate people on the planet, 270m of them in India but illiteracy is everywhere. Lots of folks use devices that don't support their native language.

Phones designed in Helsinki increasingly get used in markets where there's much less structured (in-school) learning, like Brazil, India, etc. But there's also unstructured learning: visual observation, aural, tactile stuff. When most people talk about literacy they mean textual literacy. There also proximate literacy - using the literacy of those around you.

Most people propose an iconic interface to solve the problem. But icons are just another language. Icons need to be learned, are difficult to learn without support from text prompts, and need to vary across markets. They can be part of the solution, but don't solve the problem.

To what extent is textual literacy a barrier?

Nokia did 3-4 years of research in India, China, Nepal, etc.: home visits, interviews, shadowing, observation. Looking at where text prompts were barriers. How do illiterate people use TV? How do they tell the time? Use mechanical objects? Illiterate people have textual objects in the home, like calendars: how do they work with them?

Tasks involving time and contact management: how do you manage your contacts if illiterate? Know you're being paid enough? Millions of people do this daily.

What did we learn?

Illiterate people work long hours. 5-9, 7 days a week. These guys need to transcend time and space more than the rest of us. Literate tasks require assistance and more time. It involves giving up a lot of privacy. It's all possible, just not practical.

They can operate handsets, make local calls, answer calls. Barriers are national calls, editing, management. They tend to carry physical contact books.

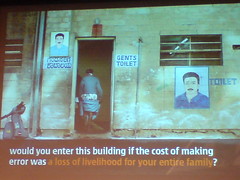

Risks and consequences: how much trial and error can illiterate users do? There is a cost to expecting users to explore (poor mental models, risk of changing settings and altering phone).

Context helps us make decisions. How much contextual info can be provided on a phone interface?

What tasks can we delegate to others, to technology. The illiterate are like the very rich in that they have support for communication tasks: from a task-process design POV it's very similar.

Illiterate users are like us, only more so.

Q: What did it look like (the resulting phone)?

A: The interface looks like the current handset experience, but with lots of small incremental experience. Can't show you the product.

Q: What's your take on the Motophone? Is this the easy path?

A: It's a simplified device. I can't judge it. First product actively marketed as being appealing to illiterate people.... there's a social stigma here, will they go for it?

I must download this presentation and make everyone@FP read it.

LIFT07: Keynote, Florence Devouard, Chair of the Board, Wikipedia

February 08, 2007 | CommentsThe setup here in the conference room is very good indeed. Desks, comfortable chairs, power at every point, and wifi that seems to cope with everyone.

LIFT 07 Keynote: Florence Devouard, Chair of the Board, Wikipedia

Some themes for today: collective intelligence, collaborative creativity, ICT in education, the digital divide, is there a risk in going too virtual.

Show of hands: about half the room have edited a Wikipedia page.

"Imagine a world in which every single person is given access to the entire knowledge of humankind"

First barrier to remove is the linguistic barrier. "We write in languages which have no encyclopedia". Second is removal of a commercial barrier: making it free as in beer and free as in speech. Wikipedia can be re-used as you wish.

Not everyone has a computer. Lovely slide of Skeletor editing the "He-man" entry on Wikipedia.

Wikipedia in the top 10 visited sites in the world, above Youtube, Fox, etc. We plan to print and distribute books.

Show's the logo of the Wikimedia Foundation: "no-one knows about it".

3 advantages of Wikipedia over traditional encyclopedias:

- Collecting data locally or globally

- Manipulating huge sets of data

- Reactivity: commentary and updates to the information

We have unlimited space today. There are no limits to information sharing. Before Wikipedia there was a notion that knowledge has boundaries: that some of it is relevant, other stuff is irrelevant. We no longer have to determine what's relevant for inclusion into the encyclopedia: it's about what's relevant to you.

We try to hand out complete, factual and relevant information - it's up to readers to make up their minds. Most web sites have an agenda... e.g. web sites about GMOs tend to select what information they will present to you, rather than helping you make up your own mind (I found exactly this when researching Landmark).

"The culture" - it's about empowering individuals. They used to get panicked support calls from novice users worried that they could edit content on the site, thinking they shouldn't be able to. Similarly they get calls from people saying "such and such a page isn't correct". The answer? "Go and fix it for yourself".

Wikipedia is about "a priori trust": "we open the gates rather than closing them". We can block vandals, but by default we consider people to be good. This is quite different to the rest of society.

"The problem about Wikipedia is that is just works in reality, not in theory" - Stephen Colbert.

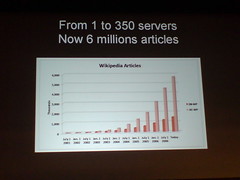

Growth: from 1 to 350 servers, 6 million articles. "We need $5m". Currently reliant on gift economy: donations from individuals, on average $20.

Q: You mentioned that the Swiss are the most active citizens on Wikipedia (relatively speaking)?

A: We have figures for articles in each language and readers, but little about contributions (as they can be anonymous). We have 50k accounts created, which (obviously) doesn't include anonymous people.

[more talk about financing of the service]

They have enough finances to keep them going for another 3 months. We're not here to make money or to be sold - we're here for the common good.

Q: How much of a problem is security or vandalism? Are there parts of Wikipedia so vandalised they can't be used?

A: Basic vandalism is not a problem. We can block large-scale changes ("this article sucks"). More of a problem are slight, small changes (e.g. changes in dates), people trying to edit their own articles (e.g. politicians removing embarrassing facts), or commercial content (not so much spam), and using sites like MySpace as sources.

Florence joined Wikipedia just before the Iraq war, and as a predominately English language service we found ourselves presenting an American-biased opinion. She had to edit the site anonymously (as she's French and that wasn't a fun thing to be when talking about Iraq ;))